Ansel Adams: A Life of Preservation, Photography and Wilderness

Visitors are immediately immersed into Adams’ vision upon entering the exhibition. His 1940 photograph, Jeffrey Pine, was taken in Yosemite.

“I knew my destiny,” Ansel Adams wrote shortly before his death in 1984, “when I first experienced Yosemite.”

The grounds were blanketed with wildflowers. Sequoias sat atop a looming cliffside. A veined leaf flew in the wind, and a mirrored moon winked. It was picturesque.

Adams left the 1916 family trip with two souvenirs: a Kodak No. 1 Box Brownie camera and a connection to the environment which would define his life’s work as one of the most influential landscape photographers of the 20th century.

A mystical devotion took root in the 14-year-old Adams, and he tended to it with visualization, his creative process which was based on what the environment looked and felt like to the artist.

American photographer, Cedric Wright (1889-1959), took this photo of Adams working in Yosemite in 1942.

Visualization allowed Adams (1902-1984), American landscape photographer and environmentalist, to capture scenes of untouched Western wilderness through thousands of bold, black-and-white images. The Harry Ransom Center’s ongoing exhibition, “Visualizing the Environment: Ansel Adams and His Legacy,” examines his enduring impact on the fields of environmental photography and preservation.

“The first step toward visualization,” Adams wrote, “is to become aware of the world around us in terms of the photographic image.”

His process laid the groundwork for the exhibition, which shows how photographers have visualized the American environment, before, during and after Adams’ time.

“Visualizing the Environment” places Adams’ work within a greater context, according to Stephen D. Hoelscher, Ph.D., faculty curator for photography at the center, by arranging his prints alongside that of his predecessors and successors.

“He is not working in a vacuum,” Hoelscher said. “He is part of a long continuum of people who have documented the environment.”

Hoelscher, historian and Stiles Professor of American studies, directed the exhibition to follow those who navigated the field of environmental photography in Adams’ wake.

Nuñez creates the mordançage solution in UT’s Photography Studio while referring to Environmental Photography: A Handbook of Techniques.

Many photographers who inherited the legacy of Adams instead chose to concentrate on what remained absent from his visualization — an environment impacted by man.

“In many ways, a lot of the goal is the same: to help people understand the importance of the environment,” Hoelscher said.

On a parallel coast in Miami stood Melissa Nuñez, a modern photographer entranced by an abandoned industrial lot.

In her work, Nuñez, now the manager of UT’s Photography and Media Lab, focuses on how American industries have degraded environments and created ruins.

“Our landscape has been changed and altered in different ways,” Nuñez said. “And some of it’s not for the better.”

Through a film manipulation technique called mordançage that she found in Environmental Photography: A Handbook of Techniques, a new imagining presented itself.

The formula uses copper chloride, hydrogen peroxide and glacial acetic acid, which are the same hazardous wastes buried beneath the industrial spaces she photographs, to mimic the deteriorating landscape.

The image rests in the chemicals, and the photographer is able to manipulate the pigmented parts of the image to create the eroded effect seen in Nuñez’s work.

Before settling into this style of photographing the landscape, Nuñez had worked with different subjects since being introduced to photography in high school.

For Nuñez, lecturer of studio art and photography, students should acquire an expansive photographic skillset and understanding of the field’s history.

Nuñez didn’t define her vision as a landscape photographer until she had learned of “New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape,” a 1975-1976 New York exhibition which signified a departure from the traditions set by Adams and his contemporaries.

“The more knowledge you gain,” Nuñez said, “the better photographer you become.”

As he neared the middle of his career, Adams, who was self-taught, exceedingly valued education, both in photographic nuance and the general field.

Portrait photographer Fred Archer and Adams designed the “zone system,” a technique which uses 11 black-and-white zones to preserve the full tone of an image, in 1940. He began to teach this method in annual workshops.

That same year, Adams helped to establish the first curatorial department at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Adams returned to the California coast in 1946 to found the first photography school, now known as the San Francisco Art Institute.

Photography was recognized as a legitimate profession and fine art through Adams’ work. Using visuals to inform and express became more commonplace.

“When we think about communicating using a visual, it can be much more persuasive,” said Lucy Atkinson, Ph.D., expert in environmental communication.

Through the field of photography, Adams set out to expand environmental consciousness.

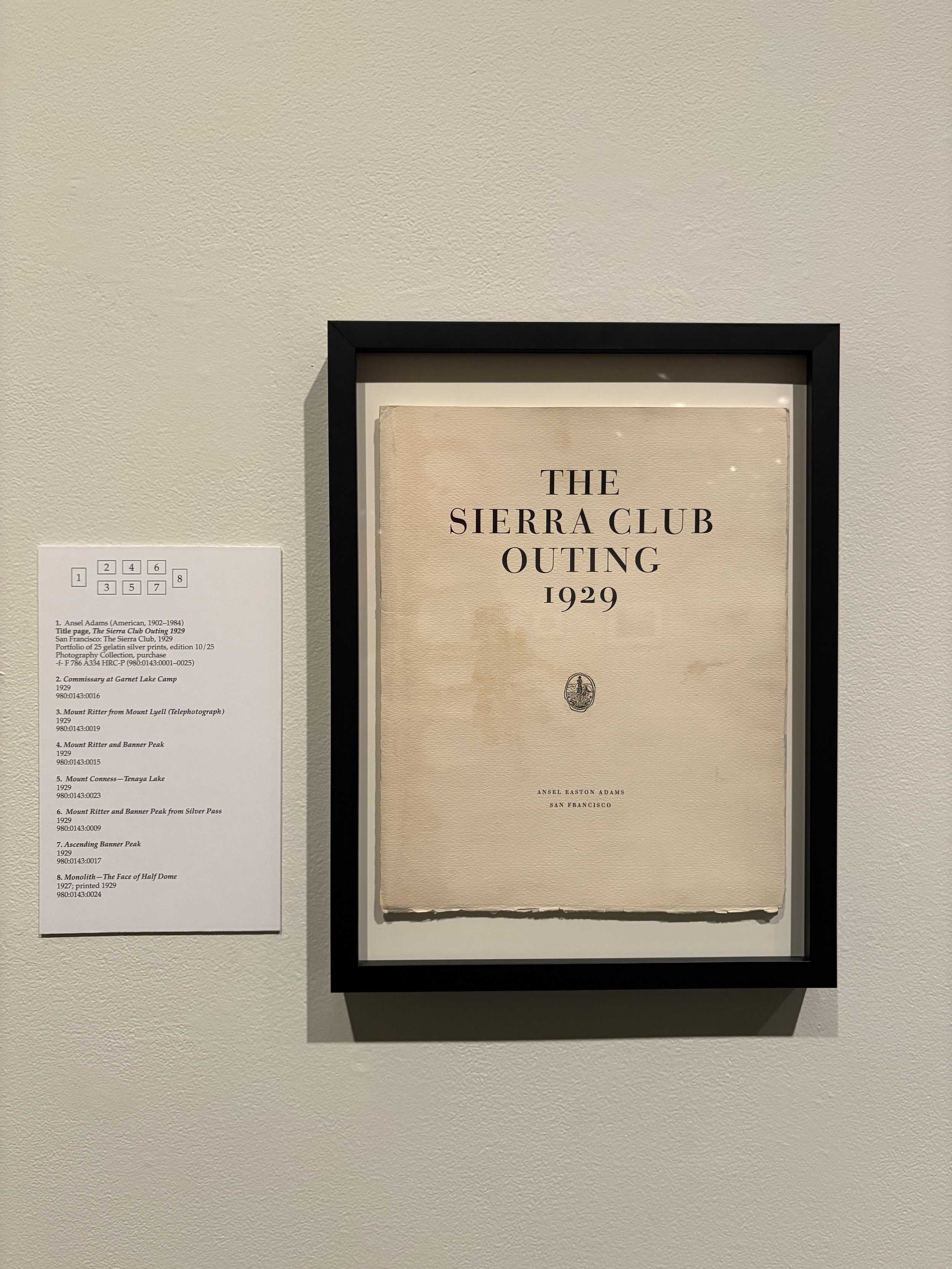

This is the title page of The Sierra Club Outing 1929, a portfolio of photographs taken by Adams during his time as the Club’s official trip photographer.

His time spent as a director of the Sierra Club, an environmental organization founded to protect the wilderness, proved instrumental in the passage of the 1964 Wilderness Act.

The act established the National Wilderness Preservation System, which encompasses more than 111 million acres of land. Public exposure to wild spaces increased, but the balance between accessibility and conservation grew tenuous.

“The problem with environmental issues is that, in a general sense, they can feel very distant from us,” Atkinson said. “We have to find ways that resonate with people.”

For Adams, natural beauty was an obvious point of entry. He hoped to present the environment to people in such a way that they would then be inspired to work toward its preservation.

In his 1975 Albright Lecture in Berkeley, California, Adams identified this response to natural beauty as “one of the foundations of the environmental movement.”

Adams did not invite meaning to his work until after he took the picture. His only goal would have been to capture the most beautiful photo possible, and later align it with an environmentalist ideal.

“The way we frame the issues,” Atkinson said, “influences, then, the solutions we think we should come up with.”

The social construction of nature, as described by Atkinson, is an idea where understanding of the environment is tied to cultural interpretation and individual perspective rather than objective facts.

In his 1983 book, Examples: The Making of 40 Photographs, Adams wrote of his vision as one that included “scissors and thread, grains of sand, leaf details, the human face and a single rose.”

Preservation remained the focus of his work, and it moved beyond protecting the physical domain into the capturing of a moment — a feeling — which inspired Adams for over 70 years.

“His photos are just so beautiful,” Nuñez, who was influenced by Adams’ work, said. “It really draws everyone’s attention to look at them.”

Adams cultivated national awareness of the environment through his sensitive, authentic vision of the land he pictured.

While a beautiful photograph cannot provide absolute environmental understanding, the curation of “Visualizing the Environment” is centered around a simple truth of photography.

“Documenting the world as it is,” Hoelscher said, “can play a role in helping us understand these important issues.”

Minick’s Woman at Inspiration Point from the series Sightseer was taken in 1980 and later printed in 2019. It is one of the last photos in the exhibition.

The center enhanced this understanding through a Geographic Information System, which embedded 3D-renderings of the environment photographed along with analyses of the work, for people to engage with after their experience.

At the end of the exhibition is a corner with two photographs of Yosemite.

The first is Roger Minick’s 1980 photograph, Woman at Inspiration Point, from his Sightseer series. A woman donning a “Yosemite” scarf looks ahead. The immediacy of adventure awaits, but for now, she observes.

Burnt Forest and Half Dome, Yosemite, a photograph taken by Richard Misrach in 1988, is the second. A lightning strike the year prior left a desolate, dystopian landscape. Scarred and standing, the trees remain.

Less than 20 miles south of these Yosemite scenes is a forest which was preserved by Adams first in photo, later in legislation.

Misrach’s 1988 photo, Burnt Forest and Half Dome, Yosemite, was printed in 2024. It is one of the last photos in the exhibition.

Shortly after he died in 1984, the land was expanded and renamed the Ansel Adams Wilderness in his memory.